Upon her confirmation as Secretary of the Interior, Deb Haaland launched an investigation into our country’s history of boarding schools for Native Americans. In response, Congressional Democrats asked federal agencies to create infrastructure to support Indigenous groups that will inevitably experience trauma and grief as the investigation gets underway. Such infrastructure could include subsidized counseling or a staffed crisis hotline – anything to lessen the emotional impact of the research.

But what will Haaland’s probe uncover?

In 1860, the Bureau of Indian Affairs transitioned Fort Simcoe in Washington State into an Indian Boarding School, designed to assimilate Indigenous youth to American culture. This re-education emphasized different aspects of Protestant ideology, including the importance of private property, the nuclear family structure, and material wealth. Additionally, teachers taught students the English language, simple mathematics, and the arts. Given these institutions’ goal of overruling the traditional Native American way of life, it’s no surprise that Christianity was a recurring theme throughout it all.

In just 20 years, the U.S. commanded 60 such schools for over 6,000 students. Teachers instilled strict regimentation, according to previous investigations. After all, a strictly structured life was the cornerstone of white America at the time.

All these themes directly contradicted Indigenous values and culture. Most tribes believed in communal ownership of the land. The idea that someone could own part of the land and keep others away from it was totally foreign to Native Americans. Rigid individualism, however, was central to the boarding schools’ purpose of obliterating the Indigenous way of life.

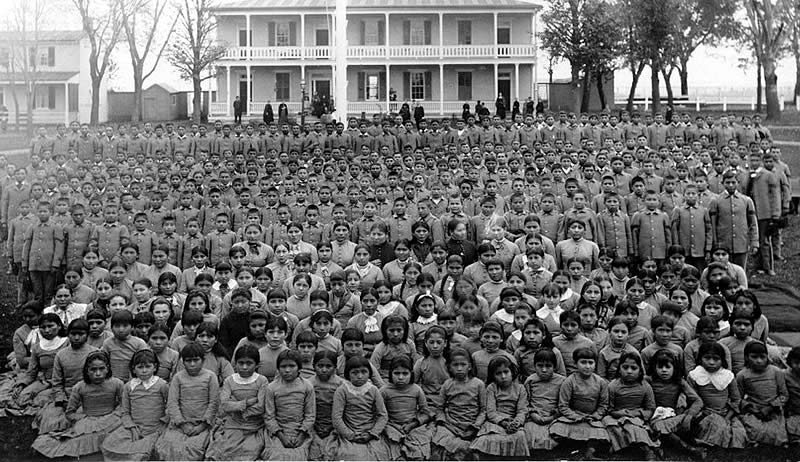

Col. Richard Henry Pratt is among the most well-known proponents of total assimilation. Pratt established the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, pictured above, where he served as headmaster for over 25 years. As leader of the country’s most infamous boarding school, Pratt was the central figure of the larger effort to assimilate Native Americans.

His motto was “Kill the Indian, save the man.”

In his effort, he sliced off the traditional braids of young Indigenous children. Pratt’s employees replaced their students’ birth names with white, mostly Christian ones. They similarly forced students to eat white foods and adopt the “appropriate” utensils. Lastly, and perhaps most disgusting of all Pratt’s measures to dehumanize children, the schools forbade students from speaking their native languages. Classrooms applauded colonizers like Christopher Columbus and endorsed the myth of the “model minority,” such as those that took part in the first Thanksgiving.

It’s apparent why our lawmakers felt the need to allocate funding toward helping Indigenous groups grapple with this painful history. An attempted total annihilation of Native American culture is not a light subject. Congressional Democrats’ call for substantive emotional support is a recognition of what it takes to embrace reality. It takes more than recognizing the facts; it requires empathy.

We must give communities of color time to grieve their losses throughout American history. This is especially true in instances of erasing a community and culture. Stories like the Tulsa Race Massacre and those of Indian boarding schools can evoke trauma and it’s our job to be cognizant of that potential effect. We cannot simply ask minorities to “move on” and “get over” history when it still impacts their communities to this day. Surely, there is room for humanity as we move forward in public policy, together.